A FEW NOTES ON THE ORIGIN OF THE NOVEL

Growing up in Hobbs, New Mexico, I once heard that in 1928 Amelia Earhart made an emergency landing on the town's one street and caused quite a stir. Decades later, learned the event happened during her first effort at a solo transcontinental flight, and, as biographer Susan Butler tells it, “The townspeople helped her fold up the wings of the little Avian and move it to a safe place for the night..., fed her at the Owl Cafe, found her some gasoline, and gave her a bed. The next morning, she took off....”

I researched the lives of a good many aviatrixes of the era and learned they were as deserving of attention as Earhart. I didn't want to write a fictionalized version of Amelia Earhart's life because I was as interested in the lives of the inhabitants of this Western village as I was of the pilot who set down among them. So, my "unfamous" fugitive pilot Katie Burke took over that role.

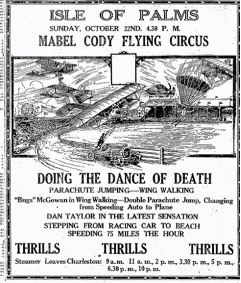

Poster for a flying circus that Katie and her parents might've belonged to

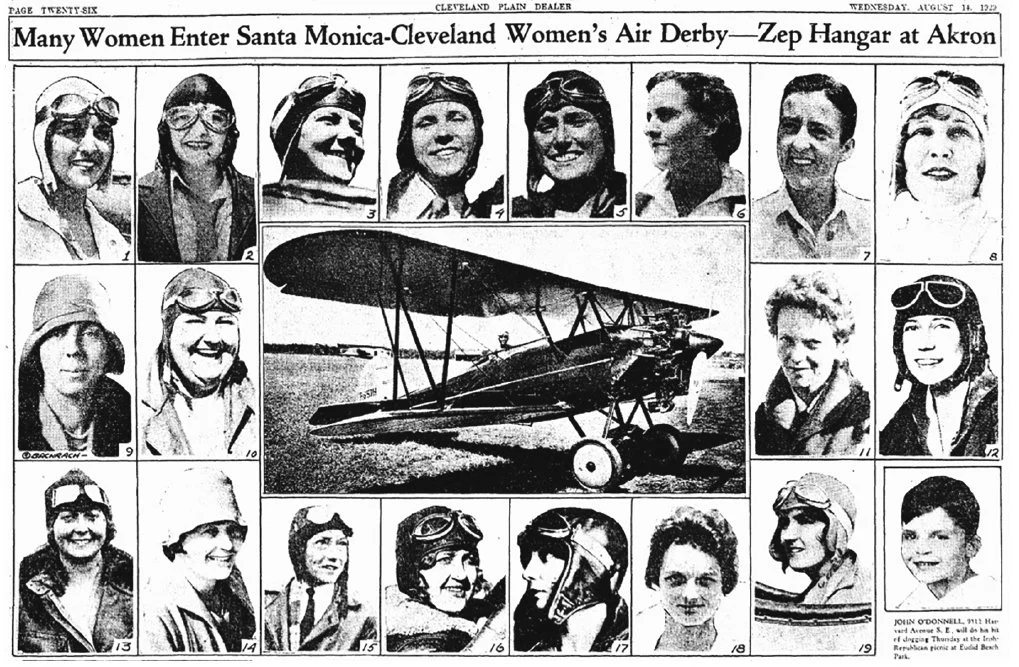

Phoebe Omlie: One of many dashing young aviatrixes of the period

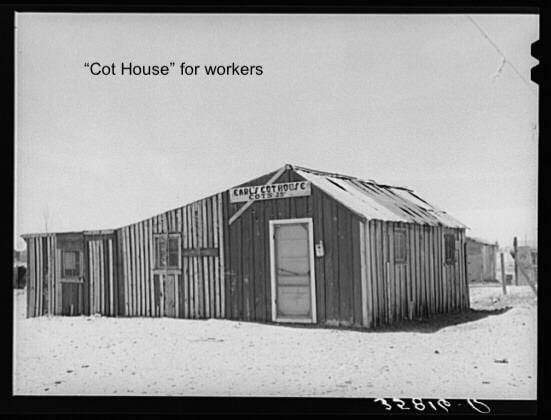

Photo of Hobbs NM ("NoName") early 1930s

FIRST CHAPTER OF GIRL FLEES CIRCUS

ARRIVAL

1

The aviatrix’s brand-new moniker was Skippy Baker. She’d dropped it on a farmer whose field she’d landed in last evening, but she’d considered others – Marvella Gold, Harriet Harley, say, or Betty, uh, Armhart? The name had to shine like a screen star’s billing but not sound made up. Tinkering with names was a pleasant pastime while she piloted the Travel Aire through a clear, mild morning over stretches of West Texas. She’d never seen such open country lidded by that vast a sky, and the craft ate it up. With the railroad map spread on her lap and the twin shining rails two thousand feet below guiding her as sure as a compass, she sailed past Abilene just after noon, pleased to gain confidence in the airplane, getting to know its in-flight quirks. She knew the specs by heart – where some girls might scribe the name of a crush in diaries over and over, she sketched views of the fuselage from all angles. She admired the aircraft beyond all reason, and on this third day out the vibrations of the Wright Whirlwind 9-cylinder radial coursed through her veins like whiskey shots. Soon you'll be a crackerjack pilot, claimed Curly, and she could remember his grin and the two thumbs up when she’d done her first solo. (All before squeezing her heart like a marshmallow in his fist.)

But those railroad tracks ran out on both the map and earth. All on the compass now. The day went hot, the air boisterous and rowdy, and the craft turned from a bird into a butterfly -- no more straight ahead steady-as-she-goes, but up and down and sideways, a leap over here and another over there like a drunken dancer, then a wave upending her nose into a stall like a boxer taking an uppercut to the chin. A sudden elevatored downdraft drop put her stomach in her throat and a fist of fear clutched her heartbeats.

And what had begun as a rude smudge like a bruise on the horizon now pushed rudely at her as she fought to keep the aircraft on a heading.

Uh-oh. Curly, regaling compañeros about these big burly storms out here. Like an ugly dirty iceberg in the sky, and you’ve lost your gee-dee paddle and the current’s rushing you right into it – you can’t go over ‘cause it’s just too darn tall some of them 40,000 feet, and too damned pardon my French honey wide to go around, so’s yer lookin at how the bottom of that black mass seems nice and level and flat at about seven eight thousand or so and you’re figgerin on just sort of gliding under it, but what you don’t know is the updraft on those monsters can suck your little crate right up into its dark black heart and zoom you up like a scrap a paper in a whirlwind and spit you out way over whatever ceiling the specs on your craft might claim, air too darned thin to fly in or to breathe and next thing you know you’re blacking out and the little coffin that’s wrapped around you’s headed straight down, and if you’re lucky you’ll wake up soon enough to pull out and keep the nose from digging a twenty-foot hole in Mother Earth.

Taking quick glimpses of the map she tried to pair something on the paper with its like below, but instead of landmarks nameless gulleys and miles and miles of cruelly featureless plain. No hills, mountains, highways, railroads, rivers, or lakes, only the seemingly endless and threatening sky looming ahead.

She’d never encountered a storm this huge – the ugly dark strato-cewm-you-loahs like Himalayan peaks shooting up to she couldn’t guess the elevation, impossible to top them – the craft officially had a ceiling of 16,000 feet, and just like he said the air there was far too thin to breathe and most likely only half the height of what she faced, and besides, oxygen hadn’t made the list of things snatched up in her hasty departure. Oh, this son-of-a-biscuit-eating storm – was it a tornado?? It might tear the craft apart, and she didn’t know whether to try for a forced wild landing on unknown ground and wreck or get herself ripped to shreds while aloft. Oh, why oh why!! You stupid little crud knuckle! You thought you could do this? What would Curly say or do? Hang on?

Her hands might’ve shaken had they not been welded tight to the stick. Then the headwind came hard at her and not even that big J5 could do much more than suspend the ship as it shoved against the front, marking time mid-air, rain pelted her windscreen and drenched her, the airplane shook and shuddered, dipped and see-sawed side to side, and it was only by the keychain Curly had hung from a knob on the panel that she knew she was rightside up. It was crucial to keep the wings level and the craft from turning without her knowing, but lost inside the horrendous rain without horizon or ground to judge by, she had to trust the turn indicator and her altimeter to stay aloft and true. Curly said he knew a pilot strapped a half full pint of whisky to the panel as a level and when sloshing turned it useless he drank it. Watch your tach and air speed – if the speed goes down but the engine revs up you’re likely heading uphill, if your tach backs off and your air speed jumps you’re probably in a dive. If the wind in the struts start to whine and sing, you need to pull her up or look for a hole in the cloud floor to dive into.

The blithering snot-booger rain turned into stinging flecks of hail – would it tear holes in the wings and elevator? Would she go down like a tattered kite? The upper wing shielded her a bit, but the prop wash peppered her with pellets of ice, and she was shivering terribly in her coveralls.

Holy malarkey, oh my dear Heavenly Father! Please let me live through this! If you do, I’ll… turn myself in!

The storm pummeled her on and on, she wrestled it like busting a bronc, and when at last she spied a glimmer in the west she figured she’d fought her way to the backside. Within minutes the air was sweet and calm and clear, cooler now from the rain, water on the wings and the windscreen glistening. Her breathing slowed, though she still trembled, and she banked right and left a bit to prove she was master now. Soon the air was friendly enough that she took big sloppy slugs from her water jug and ate an apple the farmer had blessed her with this morning. Then she unleashed her harness, wriggled free of her bottoms and jammed her pee-pot underneath her.

Resettled, she squared her shoulders. The storm was all behind her. She sighed, deep, swiped her goggles with her sleeve, settled back into her pilot’s posture. She was drenched but knew the warming air would dry her. Her compass showed that despite the tumbling and pitching, she still roughly hewed a southwesterly line. All seemed if not well at least a lot better. In fact, darned if she didn’t feel a little bit, well, proud now! A story she could tell in the hanger lounge. Beat a big storm and lived to tell about it!

As for the promise in the prayer – well, all the danger wasn’t over, right? And so didn’t her contract with the Lord include safety clear to Los Angeles? If you promise if I live through “this,” who’s to say what the length or breadth or depth of “this” is?

She looked down to read the map.

Gone! Flat blew out of her lap!

A frisson of fear zapped her nerves, but she slapped it back. That railroad map wouldn't be much help now, anyway. The flat terrain still lay as featureless as before – just a big brown table studded here and there with stunted trees. The dash clock showed she’d been aloft a little over six hours. The ship boasted a range of 650 miles on 67 gallons, but that depended upon cruising constantly at 103, and though she’d pushed the craft along earlier, having bucked the head wind through the storm made it impossible to calculate how far she’d gone and how far she had to go before her next check point, Pecos, Texas.

The fuel gauge needle was tickling the Empty bar.

Also, she was running out of afternoon. In all that trackless waste a half mile beneath her wheels, could she spot a stretch suitable for putting down? But then what? She might as well set down in the Amazon, where the last thing the natives might offer would be a barrel of high-test gasoline. Here, unless someone saw her alight (or crash), she’d have no notion of which way to walk or how far. Cowboys might one day ride up on her desiccated corpse. Headline in the paper: GIRL FLEES CIRCUS! And below - Bones Found in Desert.

It wasn't like her to take the gloomy prospect when a sunny one lay handy. But that native cheerful outlook got sorely chafed as the miles rolled on without any sign of habitation; meanwhile, that needle got tired of tickling the Empty bar and just laid its head down on it like a pillow.

Just when hope became a frayed rope about to part, she spotted a thin, meandering road hardly wider than a wagon trail going South, so she banked low to follow it. She took heart that the ruts were well-worn and clean of weeds She sailed over a truck trundling North against her flow, and the dust plume off the wheels scurried sideways and showed the wind was Westerly. Within minutes, just as the engine hiccupped once, on the horizon up popped several buildings lined beside the road, and a bit to the West, what looked to be a wooden oil derrick. That might mean fuel! Guess the Lord had no quarrel with her quibbling about the terms!

She chanced one quick low pass over the settlement to check for obstacles in the only street – it was empty – and she read the plume of exhaust from the drilling rig’s engine like a wind sock: she’d be landing with a cross wind, a stiff one maybe, and she’d have to sideslip the craft to keep it on that narrow line, all the harder when the sputtering engine would be little help. She banked and turned and came in from the South. Her luck had held! Not just a place to safely land but also maybe she'd get fuel, supper, and a bed – she was suddenly bone-tired and utterly drained, and she eagerly anticipated rolling to a stop and climbing down to stretch and….

Damnation! A Model T rolled out into the street and wheeled right into her path. She yanked the stick back and hoped she had speed enough to hop the thing without stalling –

2

Mabel was sorely shamed her auto caused the accident. Her father had bought her the Ford Model T “Tin Lizzy” back in ’24 never dreaming she’d use it to move herself all the way from Cincinnati to somewhere way out West. Her mother feared she’d wind up with a cowpoke and never come back. Besides, everything there must be so primitive. Lying, she assured them she had electricity and didn’t mention that a lack of plumbing meant she had to do her business in an outhouse behind the church/school along with her students and whatever town folk found themselves beyond reach of their own privies.

She’d claimed this post would be only a year. She didn't tell them it was on the way to further West. (When she’d heard Al Jolson sing “California, Here I Come….” something swoony crept over her like a cozy blanket. Palm trees, oranges big as softballs, and ocean waves – lots of ocean waves – swarmed behind her eyelids.)

And yet now she was about to start her third school year. The Golden State’s beckoning call had faded, and less often she insisted to herself that she wasn’t marking time or just saving up to go. That first year was rough, though. The “school board” – a dozen ranchers, farmers, and merchants who’d pooled their money for her salary – had put her up in what they hilariously called “a cottage” but was hardly more than a lean-to attached to the hip of the settlement’s lone café. But even when some said pity she had to live in “a rebuilt pig pen,” somebody pointed out that she’d turned down Arabella Bohanan’s offer to lodge in her handsome Spanish hacienda.

When the board begged her to stay, they enticed her with a ream of outlandish compliments, higher pay, and better digs: everybody pitched in to knock up a cozy cabin alongside what was called “the church” due to a structure on its roof that might be a steeple or a miniature oil derrick. A service did take place first Sunday of every month when a preacher of any denomination would circuit by. Usually, though, pews were shoved against the walls to accommodate the dozen school desks or when folks had a yen to put on a rowdy hootenany with a motley trio who played wash-tub bass, a “gittar” and a “fiddle,” all three of whom distressed Mabel greatly with their nasal yodeling and habit of drooling “baccy” spit onto the wooden floors of her school room.

With a brilliant older brother and a gorgeous younger sister, she’d been the invisible middle child, the one least talked about and from whom the least was expected. She’d gone off to Stephens for two years without hardly a soul missing her. On Mabel’s first visit back to Cincinnati after a year of teaching out West, her sister, recently debutante-ified, had badgered Mable to bob her hair and buy step-ins and an Empire-waist dress in an effort to slim down her bust and hips to comply with the current boyish fashions. Felicity also scolded her about being out in the sun so much – Mable's skin looked “like leather.” '

Out here, no hair stylist existed to maintain that fashionable bob; it grew into unruly bangs and page-boy curls then just a long mess draping over her shoulders that she dealt with the way women here did: tucked under a hat, pinned up in a bun, swirled into what might look like a cow patty atop her head, or tied back with a comely ribbon. When they felt a need, the women cut their own or each other’s hair with sewing scissors.

Surprises had held her here. One - she was far from invisible. She taught a dozen or so students 8 to 15, and she was respected by almost all and even adored by a few. Her opinion on matters big and small was valued – she was an ambassador of a larger world, someone who’d been to college, had lived in an Eastern city, owned books, could recite poetry by heart, practiced pretty penmanship, and by default inherited the traditional “schoolmarm” virtues of a superior moral sensibility and judgment, so people often sought her opinion.

Living here, she’d grown confident, felt her dormant self swell to fill the new, expanded borders of her life.

Why are you going back? Her baffled folks had asked that first visit home.

Sky. How do you talk about sky? And does it sound moonstruck daffy to even bring it up?? Illustrated-Bible sunrises and sunsets! Ohio had sky, of course, but it was like the ceiling of your parlor: imminently useful and ever-present but hardly ever noticed. Out here the sky was everywhere, and you lived in it as if a fish in an ocean of air. The settlement had but one building over one story, so nothing manmade obstructed your view of the heavens day or night. It had a hundred colors – from the deep lavender just after sunset and the later inky charcoal to the blistering white on a summer noon that peeled your eyeballs back. And at night – at night! Here on the plains deep after the sun lay down to sleep the sky asserted itself with a magnificent and admirable arrogance, strewing buckets of stars on an overhead screen, everything adazzle and alive. Make you gasp, reel, and brace yourself against the nearest solid object. It seduced her into studying – of all things! Who’d have thought? – astronomy.

And then the daytime sky had myriad moods, many weathers posted on the compass points of this great expanse – you’d note a thunderstorm on the far horizon marked by curtains of surly gray rain, while, turn a tad to the north or south, and the horizon looked as serene as a preacher’s wife.

Below the sky the terra was humble, scrub oak and sandy hillocks, mesquite thickets, native grasses – never an actual tree unless one had been planted – and the earth itself ruddy in the banks of arroyos where the water plumed and spumed, tumbling boulders when a rain did finally come.

And you could spook your backhome folks right good with tales of rattlers and tarantulas (What’s that? Well, a spider big as a BASEBALL!), as well as coyotes, though they were as skittish as whipped dogs.

She'd considered learning to ride a horse but hadn't gotten to it. (Ditto hoist a firearm.) People didn’t find that strange, anyway, since she owned and operated a motor vehicle. Her Lizzie was one of a half dozen vehicles in the settlement, and she was generous about taking somebody to a doctor in Loving or the train station in Seagraves (and more than once a goat, a sheep, or a calf). Leonard had begged her to teach him to drive, and she’d been pleased to do that, though she’d foreseen the next step – his wanting to borrow it. (He argued he could make a trip for her, save her time and effort.)

Of course, folks back home were curious about her prospects. She kept mum because speaking of Leonard might raise eyebrows. To this point in her life she’d never had a fellow fall besmitten under her supposed spell. He had what they called a “crush,” and that was endearing and flattering. Of course, he was too young at 18 and too much like an eager puppy, but he was good-looking and sturdy, well-intentioned and full of curiosity. Pity Mabel was one of only a half dozen unattached females of marrying age around. Cruel indeed how they called him “Lonesome Lennie” behind his back. His adoration and attention were hers to enjoy, even at the expense of a nagging guilt.

Normally she’d not be behind the wheel of her automobile on a late Saturday afternoon such as this. But Louise Larsen had been upstairs above the Owl Café where Wally Jackson had finished reupholstering the seat of her one good parlor chair, and Louise had hinted to Mabel that it would be “lovely” to have Mabel come to supper, only she had to pick up her chair from Wally first. Louise was a dandy cook and Mabel wasn’t, so giving Louise and her chair a ride home was a very fair exchange.

She’d heard a sputtering motor before she’d pulled out into the street, but she’d just presumed it came from that drilling contraption behind Roy Bentley’s corral. She saw Hiram step off the porch of the Owl to peer up the street, wide-eyed. She straightened the wheel and suddenly an aircraft hardly three feet off the ground was zooming right at her windscreen, looming like a threshing machine a giant had flung at her, and all she could do was shriek, slap her hands to her face, and turtle her head into her shoulders. She heard the wind in the wings as it swooped up to avoid a crash, the motor coughing, and luckily her own engine died else the auto would’ve driven itself right into the cafe's front door.

When she sat up, Leonard was wheeling past fast on his Hawthorne Flyer, chasing after the aircraft as it jittered on.

3

The old saw that in a small town everybody knows your business got a rigorous test in the West, where a contrary frontier law holds that nobody asks your business. Case in point was Hiram Jefferson and Mildred (“Wally”) Jackson. They ran the Owl Café – he cooked, she cleaned up, managed the cash and the provisions. Nobody knew if they were married, but their spacious upstairs abode was one long room stretched to the footprint of the building, and it had only one bed. Other useful furniture took up space, but just the bed figured into people’s speculations.

Supposedly, he’d been a “Buffalo Soldiers” in the U.S. Cavalry in Texas after the Civil War and had been born a slave – they figured his age at sixty-something, but nobody could say he’d claimed that. Aside from cooking, he had a garage out back where he kept smithy's tools to shoe a horse or rim a wagon wheel. He owned an old GMC platform truck, new in 1915, and he made runs to Loving for gasoline that he sold to the hamlet's other motorists at a slim profit all considered fair. Lately, he’d done welding for the driller, brazing the seams of the casing as it was pounded into the ground, and he’d made one overnight trip to Seagraves to get cable for the job.

Wally was white and somewhat younger, thin-lipped and thin-hipped, with one eye that detoured on its way to seeing something (hence the nickname), and when she talked you heard remnants of a longgone accent that people couldn’t place. Whether from temperament or their particular circumstance, they gripped their cards bosom-tight, and though Wally was talkative, she was never personal. Like almost all the women, she made many of her own clothes, though she seemed better at it than most and did odd jobs for others, such putting new upholstery on Louise Larsen’s parlor chair. Their public service included keeping the town’s only public telephone. It was posted on the cafe's rear wall, and a side table stood there with a big pickle jar for honors-system users to drop coins into. Two other telephones were in the homes of outlying ranching families.

Now and then Hiram had “moods” whose arrivals and duration no one could account for. Sometimes, inexplicably, he might mutter, “Dark days, dark days,” shaking his head. People suspected that his trips to Loving included a secret stop for a Mason jar of illegal hootch, but since he never howled at the moon or even raised his voice, it didn’t matter, and he wasn’t alone in sneaking a slug behind closed doors. The only law man around was the sheriff at the county seat in Loving, who wouldn't rouse himself over such a trifle.

The Owl always closed after lunch, though lately they’d held off shutting down until that driller, Ralph Johnston, or his helper came to get sandwiches.

Hiram had just taken off his apron and stepped out onto the porch to sit and smoke his pipe when the aircraft’s engine caught his ear; he stepped into the street to locate it coming in low from the south, engine sputtering, and it had all the appearance of preparing to land on the one unpaved thoroughfare, but suddenly up popped a Mabel’s Lizzy square in its path. He gawked, cringing, but then the craft swooped up and over it – the word BEECH NUT emblazoned in yellow on its sliver flank - and toddled on north; he trotted farther into the road to watch it stagger away on the cross wind, slipping sideways, the engine sneezing it sounded like, emitting oily puffs of exhaust. Looked likely to crash.

4

Louise Larsen was the closest thing in the settlement to a doctor. She’d grown up in Kansas City on the Kansas side near a veterinary office, and as an adolescent she’d hung about asking questions. The vet had taken such a shine he brought her on his calls to assist birthing calves and foals and lambs. Soon as the Big War broke out, an upswell of patriotism pushed her to enroll at the Illinois Nurses Training School attached to the new Cook County Hospital. Then she was a trainee at the Fort Sheridan Hospital #28 just as the first wave of injured from France arrived in 1919. Howard was a shell-shock and mustard gas patient; she was by his side for two weeks and felt such pity that when he asked her to marry him, she had.

Then he revealed he was a widower whose wife had died of the Spanish flu while he was overseas and that his twelve-year-old daughter, Isabel (“Izzy”), then living with his sister in Indianapolis, would be joining their new family as they moved to New Mexico where the good clean air would help his lungs and the absence of threatening noises offered a peace that might soothe his tortured nerves.

That news stunned her. Aside from how he’d kept it from her (anything else?), that already half-grown daughter seriously scarred her dormant dreams about children of her own. How to jockey around this new development? She worked herself up to asking Howard had he thought of having more children. He chuckled nervously, vaguely waved a hand over his torso, and said, “One thing at a time, darling.”

Did that mean getting well or raising Izzy?

Try as she might, Louise could not make Izzy like her – definitely not as a step or surrogate mother, and Louise’s efforts to be friend, big sister, aunt, or mentor were met with a rejection so dedicated it seemed inspired. Izzy only begrudgingly accepted Howard’s authority. She had the worst disposition of any child Louise had ever met – a virtuoso saucebox, a world-class whiner, she hated everything about living out here. Louise was once tempted to sneer at Howard, Are you sure your other wife is dead? but flogged herself for such uncharitable thoughts. After all, the girl hadindeed lost her mother and a home in a civilized place, etc.

Louise had farm wives' chores – they kept cows, a flock of laying hens, a couple of hogs and horses, a dog, and a sizeable patch of alfalfa, grain sorghum, and cotton, plus a kitchen garden. But she was also expected to school the girl. Before Mabel Cross was hired, people taught their children at home, or, if they had the money, sent them off to boarding school (especially the girls). The Larsen budget could never stretch that far, so it was up to them. Louise had hoped to pass along her rudimentary skills for nursing and veterinary care, at least, but the child was far too squeamish; she was fond of “dressing up” in an old nurse’s hat, though, and forcing their indulgent canine into playing the role of “wounded soldier,” inventing tragic love scenarios with melodramatic dialogue clearly gleaned from the moving pictures.

She’d turned 15 three years ago. For about five minutes, it looked as if she might strike up an interest in horses – more as an equestrienne than a caretaker, for sure – but that was related to wanting to curry favor with the Binkleys’ more affluent daughter. Next thing they knew she was spending too much time with a young rep of an Abilene hardware firm scouting locations for an outpost. Howard balked, protested, tried to rein her in, but the result was a note laid on her unmade bed that claimed she loved her father but yearned to be out in the world. She promised to write.

That was three years ago. One postcard from Santa Monica, California, several months after she left. Louise kept the thought Good riddance! to herself, and since Howard wasn’t one to share his own, she believed he was relieved. But when she heard him stifling his sobs in the barn one day, a wave of guilt just floored her. Then she had to ask – did I do enough? Was it because of me? Does he blame me for this? What can I give him to make up for it? Does he want another child now? Do I want one at this point? Would we be good parents? All this while she’d been careful to monitor her cycle out of respect for that one thing at a time, but also trusted her luck to the device she kept in the washroom drawer.

She’d heard the aircraft’s engine but just thought it the sound came from a motor car. She was up in Wally’s place inspecting the newly upholstered chair seat. Wally had made coffee, and Louise had bummed two cigarettes and smoked them on the spot. (Howard was dead set against women smoking, but Hiram had no beef about it.) She’d brought her of The American and Liberty magazines to trade with Wally for Time and The Woman’s Home Companion. A half dozen women were in the trading circle, and the magazines arrived at their “post office,” an apple crate in George Purvis’s sort-of general store.

Wally said, “You want this?” The Farm Journal.

“No thanks. I already know too much.”

“I’ll offer it to Mabel, then.”

They laughed. Mabel’s tastes ran to the likes of McClure’s.

Then Wally had to move aside a pair of overalls she was patching for Leonard, and that set off another round of tsk-tsking about what are they going to do about the poor boy? At 18, he was still everybody’s pet but was wasting his potential. Odd-jobber – well, he was good at fixing things, Hiram had taught him that, and it was always handy to call him when you needed an extra body on the farm. But the boy is smart, ought to be studying something like electricity somewhere. Worry about him living in that Indian teepee, though in truth his Uncle George’s one-room place behind that store isn’t a whole lot more civilized. Wally had gone back there to bring a shirt of Hiram’s that she’d remade for Leonard and my you would not tolerate that sort of dirty mess for two seconds.

“He’s getting better-looking all the time,” said Wally. Since Leonard was the same age as the runaway Izzy, Louise had once imagined them as a pair, then had snatched the thought back. Wouldn’t wish that on poor Leonard. She considered Wally’s comment. Yes, he was handsome, especially when his face was at rest. Tumbling blonde curls, grey eyes, square jaw – his mother must’ve been a Swede.

But he was so rambunctious, tripping over his own feet, and way too talkative – a happy chatterer more like a twelve-year-old than a man – so that diminished his appeal. He was fun, very good-natured, you liked him, though his stories about, say, the trouble he had fixing a flat on his bike tire or helping his uncle pluck and dress a turkey left no detail undescribed.

“It’s such a shame Mabel thinks she’s too good for him.”

“Oh, I don’t think it’s that,” said Louise. “He’s just… too young.”

“Won’t always be.”

Wally lit another cigarette and Louise was tempted to ask for a third but didn’t. “You know, that boy is strong as an ox. Hiram had him lift up one end of a wagon yesterday while he slipped a wheel on, and it was full of stuff.”

Wally had a mental list of Leonard’s attributes, and she often trotted them out one by one. Louise didn’t need to be convinced of Leonard’s eligibility as a bachelor in want of a wife. But Wally bore a stronger maternal impulse, maybe because, thought Louise, she hadn’t had children or hadn’t had to endure living with one who hates your guts night and day.

About then Hiram was hollering up the stairs, “Louise, you better come down! There’s been a wreck up the Carlsbad road.”

5

-- the craft did go leap-frog the auto stopped dead in the middle of the street, but when Katie flew down the other side of the mountain you could say it was like skiing on new snow fast and slippery, fighting the wind to stay on a line, hoping the engine had a few sips of gas left. But suddenly the airplane dipped back to the road, and her right wheel hit something and she went alley-oop, a ground loop left, digging the left wing tips into the turf, swinging up up up, then down and coming to rest half hiked up on a fence, her hanging almost upside down in the harness. She unclipped fast in a panic and tumbled to the dirt.

Her left wrist smarted. A big rip high on that sleeve showed a bloody gash on her shoulder. She clasped her hand over it and, panting, stood looking at the damaged airplane. Like being a babysitter and you turn your back and the kid you’re supposed to keep safe has fallen down a well.

She bent over to the side and puked.

Two kids stood watching her. They wore matching denim overalls, and looked like twins but one had hair in pig tails. It dawned on her that she’d hit something while landing. Her heart thonked in her chest.

“What happened? Is everybody all right? Is anyone hurt?”

“Kilt are pig,” said the boy.

She followed his gaze up the road to where sure enough a pig lay.

“Aw, Jiminy Christmas, I am so sorry!”

“He wasn’t no pet,” offered the girl.

“He run off when Pa got out the butcher knife.”

“Fugitive,” the girl said. She smiled at herself.

“Pa called him Bacon,” the boy said.

They walked to the porcine corpse and peered at it. Her legs were shaky. Her wrist was throbbing now. She felt nauseated and light-headed, the sort of woozy dizzy you got from an all-nighter on too much coffee. White noise in her brain cavity, a hissing. She turned to look back at the aircraft. The tip of the lower left wing had carved an arc in the hard red sand of the road, and the lower right jammed up against a fence post. Dimly she remembered that for an instant the ship had cocked up vertical after the impact and that had crushed and ripped the tip of the upper wing, and the elephant-ear aileron. The airplane’s unnatural posture all at once disturbed her immensely – it was like a scream you did this! and she was desperate to right it, as if restoring its proper stance could undo the damage.

Ignoring her aching wrist and the bleeding gash, she scurried to where the lower wing was jammed against the post, tried to lift it up and away but failed, then scrambled to the fuselage near the tail assembly and heaved with all her might to back the machine away from the fence.

Someone appeared beside her, shoving, grunting, straining mightily, and together they managed to free the wing and the plane settled into its normal horizontal position but cock-eyed in the road. But when her helper backed away from their task, he stumbled, and in an effort to catch his balance planted a boot right through the skin of the elevator. She winced and groaned.

“Oh, golly, sir!” He went to all fours, scrabbled under the elevator and cradled the torn surface in his lap, head hanging over the ragged boot hole. “I can fix it, I promise! I’m…” He kept shaking his head. He was a young fellow, likely her age. He’d ridden up on a bicycle that now lay nearby, the back wheel slowly turning, as if dying; her dazzled gaze flicked to where that dead pig had lain only to see it running down the road with the two kids chasing it. Everything was happening too fast and all at once.

“Oh my gosh, sir, you’re bleeding!” The fellow looked horrified. He was standing beside her now, over her.

She shoved back the tattered ears of the fabric’s tear, and they inspected the cut. She felt herself sliding away from her body while her self levitated into the cockpit. She couldn’t tell whether the cut was serious, but her wrist ached like crazy. Maybe broken?

“Thanks for the help.” He looked confused. She realized her voice had boggled his misperception of her gender. She tugged her goggles onto the top of her helmet so that he could see her eyes, her face.

By then, the accident had drawn a crowd that included three women in a Model T. One was apparently a nurse who insisted that she be taken home to have her injury seen to.

Katherine Stinson - from an aviating family in San Antonio just after WWI

This might be Amelia but that Avian Moth is hers for sure

Bessie Coleman - from Waxahachie TX. There's a USPS stamp in her honor

Elinor Smith

Amelia for sure

Early area hotel

Pancho Barnes